TANGIBLE & INTANGIBLE BORDERS IN CONTEMPORARY BEIRUT

The story behind

The first time I visited Beirut was at the 2020 New Year celebrations. Inspired by the Lebanese people’s will to change and prosper, I could have never wished for a better place to be other than here, joining the massive revolution crowds at Martyr’s Square in celebration of new resolutions and hopes. Located in Beirut’s central district, next to Al Amin Mosque and St. Georges Cathedral, the Square is one of Beirut’s significant landmarks, a historical site of demonstrations, and a symbol for the city’s diversity.

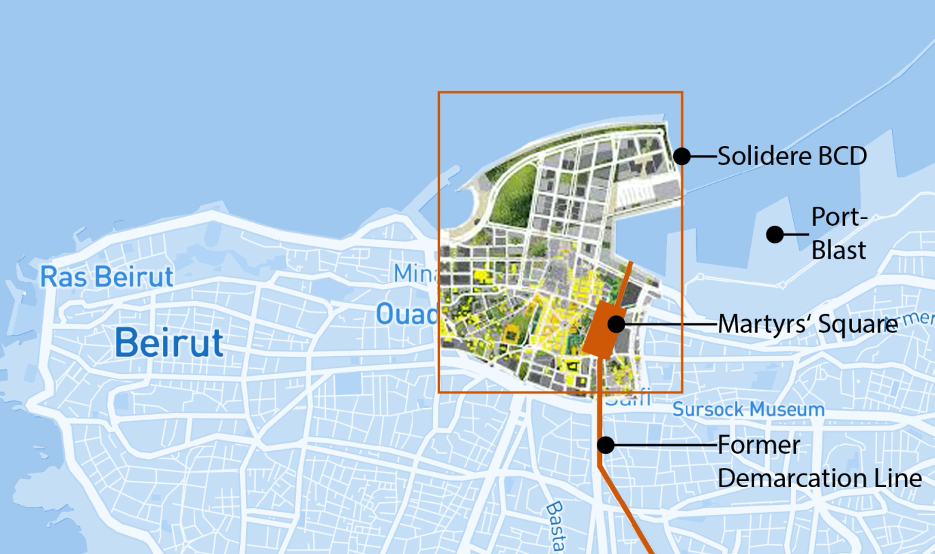

In February 2020 I moved to Beirut aiming to write my Master’s thesis in Urban Design about the intangible borders in Beirut’s cityscapes resulting from post-war divisions, and political and religious affiliations, not knowing that the next 200 days would become a compact narration of unprecedented events, unique in Beirut’s history; starting with political upheaval and public protests in October 2019, the city’s lockdown due to the Covid-19 pandemic in March, followed by an economic meltdown and a massive explosion at Beirut’s port on August 4th, sending destructive shockwaves across the city and a mushroom cloud into the air.

The day after the blast, I went to the port and the site of destruction. In my neighborhood, window glasses had been destroyed, and the closer I came to the scene at the Port, the worst it got. I walked through the adjacent neighborhoods, from Mar Mikhael to Gemmayze in the direction of the Central District to Martyrs’ Square. The scene was gruesome: cars turned upside down, bent steel frames and gates, demolished houses, and a mix of glass and blood covering the ground. The blast drastically transformed the urban fabric and brought global attention and sympathy to Beirut. As a German researcher who closely witnessed the tragic event, I took on the responsibility of shedding light on Beirut’s suffering resulting from numerous crises at several levels peaking in this tragic moment of destruction.

Beirut

Biparted for 15years, the demarcation line was the tangible border (Damascus Road) bisecting the city’s geography, reducing and homogenizing its residents into ‘West–Muslims’ and ‘East-Christians’. Officially reunited at the start of the 1990s, the borders of contemporary Beirut are rather intangible, shown through behavior patterns than physical markers in the city. “Beirut is also a city divided by many boundaries, demarcation lines, internal frontiers, some visible others not, some felt subconsciously, others glaringly perceptible, some short-lived, others nearly a century old.[…].The various territories thus demarcated add up to a very fragmented city, struggling to function as an urban entity, its population trying to cope or come to terms with the many obstacles limiting its freedom of movement. ” (M.F.Davie, 1997:35).

The Conceived of BCD

centrally & monopoly controlled reconstruction

[The] conceptualized space, the space of scientists, planners, urbanists, […] this is the dominant space in any society (or mode of production). Conceptions of space, […] towards a system of verbal (and therefore intellectually worked out) signs. (Lefebvre, 1991[1974]:38-39)

As part of the demarcation line, the end of the civil war indicated the reconstruction of Beirut’s Central District[1] (BCD) —a 140ha mega project, referred to as “the most important development project of the 1990’s” (Nasr,2015:27). In contrast to pre-war laissez-faire policies, the reconstruction plan was centrally and monopoly-controlled; a product of conceived space, the “place for the practices of social and political power; in essence, it is these spaces that are designed to manipulate those who exist within them” (Lefebvre,[1974] 1991: 222). Commissioned to plan the reconstruction and development, Solidere was founded in 1994, a private joint-stock company of property right holders and investors that exchanged the private and public land for bonds, turning them into investments.

The development pursued the vision of a modern yet ‘Utopian Beirut’. In its double function as port-city and capital, the new BCD is to become an international business and financial Centre, linked to offices, luxury hotels, upmarket living, commercial, and white-collar activities (Davie, 1993).

The characteristic narrow streets of pre-war Central District were replaced by motorways, the traditional souks (Arabic markets) redeemed by luxury shopping malls; the reconstruction attempted to generate new collective memories; a conceived space designed to represent a forward-looking national place, while deleting all signs of war.

The Perceived of BCD

a working district

The spatial practice of society secrets that society’s space; […] embodies a close association, within the perceived place, between daily reality (daily routine) and urban reality (the routes and networks which link up the places set aside for work, ‘private ‘life, and leisure).( Lefebvre, 1991[1974]:38)

Thirty years into the reconstruction of BCD, the project’s realization has generated ‘limited’ access, manifested in deluxe housing developments and insufficient public transport. The connection between BCD and the outskirts is left to private transportation, which strategically excludes parts of Beirut’s population and activities. “White-collar cadres commuting during working hours, with the area closed off at night: no shops, no entertainment, limited housing” (Davie,1993:6) —the Centre became an exclusive and almost ‘extra-territorial piece of property’.

The working schedule determines the perceived space; morning traffic peak hours filling the roads into the city, packed restaurants during lunchtime, and in the evening, the rush hour of after-work shoppers and cars leaving the working district.

The Lived of BCD

five types of urban symbolism[2] on Martyrs’ Square

Space as directly lived through its associated images and symbols, and hence the space of ‘inhabitants’ and ‘users’, but also of artists and perhaps of those, such as a few writers and philosophers, who describe and aspire to do no more than describe. (Lefebvre, 1991[1974]:39).

The emotional symbol bearers (Nas, 2011):

Branded as the ‘Paris of the Middle East[3]‘ till 1975, Beirut’s identity after the reconstruction is described as ‘a sensitized Middle East theme park for upper class population[4]‘ (Mermier, 2013). As part of the former Demarcation Line, for many Beirutis[5], the Central District is emotionally sill connected to a border between East- and West-Beirut, dominating their mental map of the city and guiding spatial decisions.

The iconic & discursive symbol bearers (Nas, 2011):

The iconic Martyrs square is named to commemorate the martyrs executed under Ottoman rule at this very place. Represented as a tourist attraction as well as landmark in literature and on web pages, the Square receives its discursive frame and meaning through narratives of its history tracing back to long before the civil war.

The material symbol bearers (Nas, 2011):

Located in the heart of Central District, the Square is bounded east, south, and west by four-lane motorways and a large scale parking lodge marking its northern limits. The second row frames densely upmarket housing developments currently under construction and two of Beirut’s most significant landmarks, the St. Georges Cathedral and the Mohammed Al-Amin Mosque. The focal point and only material symbol bearer on the paved Square is the Martyrs’ Monument in its Centre.

The behavior symbol bearers (Nas, 2011):

In the mid 20th century, the open space here used to be a vibrant venue filled with cinemas and coffee-houses; today’s square after the implementation of Solidere’s reconstruction plans offers neither leisure locations nor spots for social meetings. The observed behavioral patterns are limited to people entering the mosque and tourists visiting the square.

However, a chain of external circumstances altered the intrinsic logic[6] and the perceived functions of Martyrs’ Square; modifying the space dominated by conceived structures into a vivid place characterized by signs and symbols of the ‘lived’.

Since October 2017, Martyrs’ Square has been the site for the anti-government protests, locally known as the ‘October Revolution[7]‘. Brought on by planned taxes on voice calls via the messaging service whatsapp[8], gasoline, and tobacco, the series of civil protests, is the outcome of frustration and resistance against longstanding unemployment, a stagnating economy, and the extreme corruption in the public sector. The demonstrations against mismanagement of governance unite people of all ages, across religious and political affiliation, and social status.

The protests became permanently manifested on the square by a phoenix statue constructed of burnt down tents, in front of a six-meter high statue —a fist, stating the word > ثَوْرة < (Revolution). In March, the public demonstrations came to a sudden stop when security forces imposed countrywide lockdown measures due to the globally spreading coronavirus. Interrupted by a three-month stay-at-home order, public protests returned to the streets on June 6th, revitalizing the Martyrs’ Square. The additional economic damage caused by the lockdown and missing financial aid from the government had deepened the country’s financial crisis and the situation its people found themselves in.

On August 4th, a tragedy shattered the capital once more, when an explosion at the port, caused by 2750 tones of ammonium nitrate, destroyed property worth 10-15 billion US-Dollar in Beirut’s Centre and surrounding districts, adding more than 170 deaths and thousands injured. In its aftermath and in light of the government’s failure to prevent the lethal accident, protests erupted anew. What have so far been mainly peaceful protests, reached a boiling point and escalated into riots when demonstrators entered Beirut’s government buildings on August 8th. The Revolution and mounting anger over the blast led to Lebanon’s government’s resignation on August 10th and the visit of French President Emmanuel Macron on September 1st.

The announced protests— loud gatherings carrying symbols and signs— continued to leave marks of destruction. Manifested in burned objects, sprayed houses, and broken windows, the revolution leaves its marks on the cityscape. As the Explosion destroyed almost all windows within a radius of 11km— implying the area of BCD and the luxury developments surrounding the Martyrs’ square —, the empty frames became doors to occupy the constructions, enabling protesters to cover openings and balconies with banners, thereby giving the square as the place of the revolution a new vertical layer.

State property and symbols of capitalism that had survived past protests were demolished either by the explosion itself or in the acts of vandalism that followed— the difference has become hard to tell when walking through the Central District in recent weeks.

The Central District of Beirut, planned and conceived of as a financial and business district by Solidere has changed. The urban fabric is heavily damaged, landmarks are destroyed, offices inaccessible, commercial activities and tourism have stopped. The economic meltdown, exacerbated by Covid-19 and the destructive port blast, have led to an inflation rate of more than 70%, a shortage of food, and the shrinking and closing of businesses which have in turn prompted massive layoffs. Beirut Central District, covered by signs and symbols of a remonstrative population and destruction, has lost its glamour. How it will develop from here is unpredictable.

Short Biography

Laura Isabelle Simak, born in Mainz, Germany 1989, majoring in Urban Design at the Technical University of Berlin, finalized her Master’s thesis in Beirut under the supervision of Professor Robert Saliba (American University of Beirut) and Professor Angela Million (TU-Berlin).

She graduated in 2015 with a Bachelor of Arts in Architecture at the Technical University of Mainz; thereupon worked as a lecturer and research assistant at the university’s institute for two years.

Published in 2017 by ‘Deutscher Kunstverlag’, She was in charge of the cartographic production at METACULT, a 3-years’ transnational research project studying the cultural transfer in architecture and urban development on the case of Strasbourg.

Thereafter, she moved to Santiago de Chile for one year to work with Pablo Casals-Aguirre in architectural photography and filmmaking. She initiated her own photographic project capturing homeless people living on Santiago’s streets.

Email: laura.simak1313@gmail.com

References

Davie, M.F.(1993).A Post-War Urban Geography of Beirut. Warwick, Eurames Conference

Davie, M.F.(1994).Demarcation Lines in contemporary Beirut. The Middle East and North Africa, World Boundaries Volume 2, Chapter 3.London. Routledge

Genberg,D.(2002).Borders and boundaries in post-war Beirut. Urban Ethnic Encounters.The Spatial Consequence.Chapter 5. London. Routledge

Lefebvre, H. (1991 [1974]). The Production of Space. Oxford and Malden: Blackwell.

Löw, M. (2012). The intrinsic logic of cities: towards a new theory on urbanism, Urban Research & practice, 5:3, 303-315,DOI:10.1080/17535069.2012.727545

Mermier, F. (2013).The Frontiers of Beirut: Some Anthropological Observations. Mediterranean Politics,Vol.18,No3,376-393.Franc.Routledge

Nas, P.J. (2011). Cities Full of Symbols. Leiden University Press.

Nasr,J.L.(1996).Berlin/Beirut: Choices in Planning for the future of Two Divided Cities. Journal of Planning Education and Research. doi.org/10.1177/0739456X9601600104

Rowe, P. G., and Sarkis, H.(1998). Projecting Beirut : Episodes in the Construction and Reconstruction of a Modern City. Munich.: Prestel Print.

Saliba, R. (2004). Beirut city center recovery : the Foch-Allenby and Etoile conservation area. Göttingen: Steidl.

[1] See Saliba (2004). ‘Beirut city center recovery : the Foch-Allenby and Etoile conservation area.

[2] See Nas, (2011). Cities Full of Symbols: As a sub-discipline of urban anthropology, urban symbolism ecology explores urban space’s symbolic side. Nas separated five types of symbol bearers – emotional, iconic, discursive, behavioral, and material

[3] See Rowe, P. (1989) Projecting Beirut

[4] See Mermier, F.(2013).The Frontiers of Beirut

[5] Residents of Beirut; used by Davie (19997), Mermier (2013)…

[6] Term coined by Martina Löw (2012)

[7] https://www.lebaneserevolution2019.com

[8] The government proposed a monthly free of 6$ for using whatsapp [https://www.bbc.com/news/world- middle-east-50293636]